Music to the Ears: Opera

and Base Ball Come to Old Chicago

Baseball has been played in Chicago for a long time, a lot

of it at Wrigley Field. Before Wrigley Field, there was Comiskey Park, and

before Comiskey, there was West Side Grounds.

Before that, there was Washington Park, and before that, there was

Lincoln Park, and before Lincoln Park, there was…Opera.

Postcard. Wrigley Field, c. 1956. The Cubs host the Milwaukee Braves.

Postcard. West

Side Grounds, c. 1913. A play at the

plate.

Postcard.

Spectators crowd the field during a match played in Lincoln Park,

Chicago, c. 1908.

One day in the spring of 1863, an opera impresario by the

name of Jacob Grau brought a touring troupe of tenors and sopranos to

Chicago. The city batted its eyes at the

elegant company and swooned in delightful anticipation. Booking a three-week run at McVicker’s

theater, Grau opened a box office at a downtown music store on Monday, June 8,

and was mobbed by customers. The

impresario pocketed $4,000 in subscriptions during his first day in business

and was deluged again the next. On

Wednesday, the last of the subscriptions was sold and speculators immediately

launched a vigorous scalping trade.

A few days later, Grau inaugurated his musical festival with

a production of Donizetti’s popular Lucrezia Borgia. The divas and their

masculine counterparts on stage earned an enthusiastic round of applause from

the Chicago Tribune, and the paper was equally impressed with the

opening night parade of fashion. “The Belles

of the avenue breathe free once more,” the Tribune’s review

exclaimed. “New bonnets and head

dresses, opera cloaks, and what you call ‘ems, have all been exhibited and

admired, and Chicago upper ten is in ecstasies.”

For the first two weeks of the lyrical gala, the cream of

Windy City society rewarded the melodies of Verdi and the arias of Rossini with

packed houses. A heat wave and the

rigorous performance schedule dented the attendance figures for the final

quartet of shows but did little to mar the season’s overall success. Grau staged the twelfth and last of his

glittering sensations on the Fourth of July and then issued well-deserved

furloughs to his retinue. As the

musicians decamped for cooler climes, the city turned its attention to a more

familiar pastime—picnics.

Chicagoans in 1863 deserved a carefree day in the

countryside. With the American Civil War

passing into its third and grimmest year, the pages of the city newspapers were

blotted with dense, long lists of the dead and wounded from Illinois

regiments. Picnics offered residents an

escape from the bleak news and the busy press of urban life. Encouraging a particular excursion to a rural

spot west of Chicago on the Rock Island Line, the Tribune urged its

readers to take advantage of the chance “to breathe the pure country air, free

from the dust of the city, and the effluvia of the Chicago river.”

Resorts competed for patrons with advertisements of deep

ravines, cool springs and romantic paths in the woods. There was also plenty of room for athletic

exercise. Women and girls practiced

grace hoops, both sexes competed in foot races and archery contests, and “staid

old gentlemen” pitched quoits. Younger

men played a sport just beginning to take shape in Chicago that summer—Base

Ball.

Postcard. A family

enjoys a picnic in Washington Park while a baseball game is played in the background,

c. 1910.

The Opera House— Opera had been sung in Chicago

before 1863, and games of bat and ball had been played in Chicago before

1863. But there was something different

in the air that spring and summer, a yearning to make a bigger and better

future for the city. Both opera and base

ball gave the city something it wanted, and so the city permanently inscribed a

new season for each on its calendar that year, finding a voice in the world

with the art and flexing some muscle with the sport.

Chicago embraced the opera first. In return for its affections, Chicago

demanded a quality product from the touring companies. “We have been humbugged and victimized over

and over again, but those days are over,” the Tribune announced in one

oration. Insisting on “legitimate opera,

legitimately performed,” the paper then served notice that the city expected

all future productions to measure up to the same standards prevailing in New

York. Later, the construction of

Chicago’s first opera house prompted the paper to declare the city’s musical independence

from Gotham’s influence. “Westward the

star of Opera takes its way,” the Tribune sang in the fall of 1864. “We are at length free of New York opera, New

York artists and New York music hashed over for Western consumption.”

The New York Herald ridiculed the notion and jeered

Chicago’s opera goers:

The Chicago gentlemen are greatly troubled about the full

dress regulations. They say that dress

coats are very dear, and can be used on no other occasion than opera nights,

and they hold that frock coats, with white gloves and neckties, ought to be

allowable. The ladies are in a terrible

flutter, and every dressmaker is engaged ten deep. These rural ideas of fashionable manners and

customs are very amusing. By their very

attempts to rival New York the Chicago people admit it to be the only

metropolis of the country. We wish them

joy of Grau and their opera, and shall try to keep them posted upon all the

latest styles here.

In journalistic terms, the Tribune politely invited

the Herald to either shut up or step outside. The mudslinging between the papers had no

effect on Chicago’s carpenters and the city’s Opera House opened more or less

on schedule in April of 1865. As far as

the Tribune was concerned, the triumphal event concluded all debate: the opening of the doors granted Chicago

entry among the great cities of the world, and that was that.

Opera House Stereograph, c. 1870. Chicago’s Opera House

was a palace, and the opulent construction financially ruined its builder,

Uranus H. Crosby, an ardent city booster and generous patron of the arts who

had made a fortune distilling liquor during the Civil War years.

Opera House Lottery Ticker, 1865. On the day after Christmas of 1865, Crosby

put the Opera House up for auction, every nickel of his fortune gone and unable

to pay the bills. Concocting a bizarre

lottery, Crosby somehow regained his property from his creditors, only to later

lose it again, forever, in the Great Chicago Fire. Crosby never regained his business touch and

he died in 1903, poor and forgotten.

Squeeze Play—The 1865-66 opera season nearly ruined

Crosby, and it nearly ruined Grau, too. Fast talking with the bankers saved

Crosby. Fancy footwork in Louisville

saved Grau.

Marooned in St. Louis one day and desperate for cash, Grau

shared his financial woes with Diego De Vivo, a fellow impresario. De Vivo pondered the problem a few minutes

and then remembered a recent newspaper article.

There was a theater manager named Munday in Louisville, De Vivo told

Grau, who was fast losing money on a certain prima donna whose expenses were

exceeding ticket sales. De Vivo wondered

if a week in Louisville could get everyone’s accounts back into black ink. Grau calculated he could rescue himself and

Munday for a $5,000 fee, $3,000 to be paid in advance.

De Vivo pulled on his hat and made a beeline to the

telegraph office, informing Munday that Grau’s opera troupe was available for

six performances but omitting the price.

Munday wired back, bidding the needed $5,000 for six

performances, and De Vivo, figuring there was more to be gained, tendered the

proposal to Grau, recommending a rejection.

“Accept his offer,” Grau said, “before he changes his mind.”

“Leave all that to me,” De Vivo said.

De Vivo took a train east that night and met Munday the next

morning in Louisville. Inflating the

expenses of the opera troupe, De Vivo calmly stated that Grau needed $7,000 to

set up shop in Louisville. Munday

countered with $5,500.

“Am offered $5,500,” De Vivo wired Grau. “Telegraph me you cannot accept.”

“For God’s sake, sell,” Grau quickly answered, “and send me

$3,000.”

De Vivo ambled back to Munday’s office and breezily waved

the telegram before the theater manager, artistically concealing the contents

of the wire.

“It is as I expected,” De Vivo gravely explained. “Grau cannot sell at that price. He must have $7,000.”

“I’ll give you $6,000, and that is all I will give,” Munday

replied. “Take that or leave that.”

De Vivo lit up a Havana cigar and walked back to the

telegraph office. “I am offered $6,000,”

De Vivo wired Grau. “Telegraph me you

cannot accept.”

“You are crazy,” came the reply from St. Louis. “Sell and send me $3,000.”

De Vivo returned to Munday’s office and gave the telegram

waving routine an encore. With a shrug

of his shoulders, De Vivo told Munday that Grau was firm. The price was $7,000. Munday conceded another

$500 to the pot. With time running out

on the business day and an evening train to catch, De Vivo finally

compromised. “I will accept the

responsibility and the risk,” De Vivo grandly offered, “and split the

difference. I will close the contract

for $6,750.”

Munday signed, and Grau pocketed his $3,000 advance the next

day, back in business.

Sized slightly larger than Bowman baseball cards, Liebig

advertising cards circulated in Europe during the late 1800s and early 1900s

and often featured operatic themes. The

cards have been collected for more than a century. Top: Fidelio Beethoven (1893). Middle:

Don Juan Mozart (1893). Bottom:

La Traviata Verdi (1913).

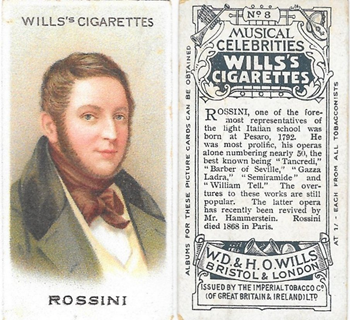

The Italian composers Gioachino Rossini and Giuseppe Verdi

were subjects of British Imperial Tobacco cards.

Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868), pictured above on Wills's

Cigarettes Musical Celebrities No 8 1912, composed 39 operas including The

Barber of Seville, William Tell, and Le Comte Ory.

Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901), pictured above on Ogden's

'Guinea Gold' Cigarettes No 63 c 1901, composed Rigoletto, La Forza Del Destino

and Otello among his 25 operas. The back

of the card is blank.

Early Innings—Chicago’s affair with base ball took a

little longer to blossom. Schoolboys had

played barehanded games of bat and ball in America from colonial times. A still gloveless but more mature and

regulated brand of the recreation emerged in New York City during the

1840s. Partisans gave it the two-word

name, Base Ball, and wrote a rulebook.

The entertainment soon spread from the boroughs to other Eastern cities

but was slow making its way west. In

1863, the number of diamonds in Illinois could probably be counted on one

hand. A small scattering of amateur

clubs practiced the game in Chicago and only the Empire Base Ball Club in

Freeport tended to the sport outside the city.

That summer, the Empires challenged any of the big city clubs to play

for an Illinois championship. Chicago’s

Garden City club accepted the invitation and fell to the Empires in a

politely-disputed three-game series.

Base Ball was wildly popular across the upper Midwest in

the years following the end of the Civil War.

This handbill is an example of the new game’s enthusiasm. It advertises an 1867 match between the

doctors and lawyers of Beloit, Wisconsin, describing the sport as The Best

Thing Yet, and confidently promotes an admission fee of 10 cents for the event.

Excelsiors—The end of the Civil War allowed the game

to flourish in Chicago. Hailing the

exercise as a superior refreshment for mind, body and soul, the Tribune

stamped its approval on base ball’s local growth:

In this city at least 500 young men, many of them members of

the “first families,” and all of the respectable class, are members of

different clubs whose headquarters and batting grounds dot the city in all

directions…Everywhere the game is a decided institution.

There was also the city’s reputation to consider, and the

nagging matter of the state crown, still jealously held.by the stubborn Empires

of Freeport.

In 1866, the Chicago Excelsiors rose to the top of that

city’s base ball rankings, based in in part on its wealthy pedigree,

maintaining a fashionable office downtown and a practice field on Lake and

May. But the team proved its worth on

the diamonds that season, knocking the Freeports off their perch to start the

year and then defeating a Detroit ball club in a memorable match that concluded

a tournament for the Midwestern championship in June. Detroit complained about its loss for

decades. In a 1903 interview, Detroit

right fielder David Barry said:

The umpire beat us.

He allowed the Chicago pitcher to ‘bowl’—use a slight overhand motion in

delivering the ball. Everybody knows we

had to deliver the ball underhand those days.

The advantage their pitcher had over us was enough to win the game.

That old grudge rankles deeply in our hearts yet.

The Excelsiors ended the year by winning the first-place

prize in a September tournament, besting a brace of well-respected St. Louis

clubs along the way and then dispatching the rival Chicago Atlantics in a

hard-fought showdown.

Dodging insistent invitations from Detroit for a rematch,

the Excelsiors finished their campaign without a loss, kings of the game from

the banks of the Mississippi River to the shores of Lake Erie, and the

unblemished record had a certain ring to it, and it made a certain noise. It sounded like music.

And thank you Russell!

NEXT FRIDAY: 1981: Part 1.....things are gonna get sticky around here. That's right, I'm talking the 1981 Topps Baseball Stickers...and album.

No comments:

Post a Comment