I quit a lot things.

I’ve quit sports teams. I’ve quit friendships. Quit music lessons. I’ve quit on TV shows and movies. Quit puzzles. Quit video games. Quit countless jobs. Quit on apartments. Quit on cities. I’ve quit on cars, politicians and patriotism. I quit collecting cards once…but I came back. One of my favorite “quits” was the time I quit my grade school varsity football team the day after the coach had three eighth-graders chase me around the track because he felt like I was dogging it. And I was. Because I wanted to quit the team. The coach was also my gym teacher, so he was there when I dropped off my equipment. He took the opportunity to tell me just what a lazy, quitter and loser I was. He was right. I couldn’t argue with him. I was born to quit.

I don’t know why I quit so many things. It’s either a them or me situation, but I haven’t been able to figure it out. What’s more perplexing to me is why I ever wanted to join something in the first place? I don’t remember any peer pressure ever coming my way. I wasn’t the kind of kid the other kids were desperate to have around them. I was an unwilling tagalong or an also-ran. Maybe my parents pushed activities on me; not to excel but to just be a part of something. I was the kid content to sit inside all day, playing with my baseball cards or watching cartoons on TV until an unreasonably older age. To this day, an idyllic summer’s day to me is to be inside with the doors shut, A/C blasting and the windows drawn.

Would if I could I’d quit on the world.

But in the Spring of 1986, I wanted to try my hand at Little League. Why? I had no idea. I was probably a secret sadist. I wasn’t satisfied enough with the bullying that I received in school, or the way the girls went above and beyond to ignore me. Maybe I was going through one of my own phases, where I felt that I needed to get out there and open myself up to the world around me. That I simply wasn’t doing much of anything but eating food, listening to the Monkees, or watching too much TV. I may have been having an existential crisis. Were existential crisis’s known to happen to twelve-year-olds?

I mean I was the kid who faked sick and skipped school the day the Challenger blew up...that was quite a thing to watch at home alone.

I begged my old man to sign me up for Little League. Admittedly, he was wary. I had a trail of unused musical instruments, crafts, etc in my path. I’d quit tee ball only two years before. The previous fall I’d made it through a JV seasons of grade school football, but I’d threatened to quit the team nearly every single week. I only stayed on because we had Gatorade on the sidelines. We didn’t have much money at home back then. Signing me up for Little League wouldn’t break the bank…but it wasn’t cheap either. The old man made me promise that if he signed me up, I’d play out the season. Sure, sure, dad. I couldn’t wait to get out on the field. Hear the crack of the bat. Smell the leather on the glove.

Full disclosure? I love baseball. But I’m fucking horrible at playing baseball. At least I was back then. I was afraid of getting hit by the ball. I’d been hit by the ball. That would’ve been in the summer of 1981. In West Virginia. The old man and me playing catch in the back yard. I moved my glove away too soon and the ball got me right in the mouth. It left me with a split and fat lip. That ball left me a traumatized seven-year-old. If I couldn’t feel safe catching a ball from the old man, I certainly wasn’t going to stand in some batter’s box, trusting the accuracy of some dipshit 11- or 12-years old throwing at me from 60 feet away. And that’s exactly what happened to me when the Little League season started. Instead of stepping into a pitch, I’d move my lead leg away. I struck out almost every at bat. This made me popular with the other kids on my team.

Guess what I wanted to do by the third game?

And why not quit? I didn’t need the abuse of vulgar kids who, while they were right about my hitting prowess, didn’t need to make such a big deal about it. If I quit I could stay home like I wanted to. My parents had bought me a 13-inch color TV for my birthday. It had a cable hook-up and everything. HBO was running The Breakfast Club ad nauseam in the spring of 1986. I could cultivate my Ally Sheedy crush to its full potential.

Or I could skip evening games, skip the ridicule, and stay home to watch Who’s the Boss? Family Ties and the Cosby Show, yearn after my hat-trick of starlets.

Then I thought about my promise to my old man…so I stuck it out. Do my best to try and make some contact so I oculd stay under the radar. Sit on the bench and chew gum. But my manager, he noticed something in me. I might not have been able to hit. I might’ve confounded him and the coaches each and every single time we went to the batting cages (I could hit at the batting cages. The batting cages weren’t 11 or 12-year-old dipshits throwing balls at me). But I could field. Boy, could I field.

Whatever fears and anxieties I had at the plate disappeared on the field. Again, I had no clue why. Maybe I felt more in control with a glove rather than standing there vulnerable at the plate. But I caught everything hit to me in the outfield. So much so that my manager put me at first base. I excelled at first base to the point where I became a starter. Much to the chagrin of my teammates, who’d rather I came in and played the requisite one or two innings they let the scrubs play just to prove to parents they were getting their money’s worth. They proved their displeasure in between innings when we warmed up in the infield, by throwing the baseballs past me so that I had to consistently give chase. Thankfully they didn’t do that during regular play.

Occasionally I got on base as a hitter. Mostly via walks. Being on base was its own kind of social stress. A lot of the time I knew the other kid playing first base. They were about as cordial to me as my teammates. Some of them where my classmates at Catholic school, so we had whatever embarrassments I’d accumulated from September to June between us. I was a fat kid in grade school who did a mean Bob "Bobcat" Goldthwait impression...so there were a lot of embartassments.

One such classmate I dreaded to see was first baseman was Tony Rizzuto.

I didn’t like Tony Rizzuto. He was a smug kid with short guy syndrome who already looked like he was going bald at twelve. But the girls liked him. Tony was good for those backhanded compliments. Like, Jay, that shirt looks good on you. Knowing damned well my fat-ass wasn’t looking good in anything. By twelve-years-old I’d had numerous daydreams of knocking out Tony Rizzuto. And I didn’t like playing ball against him. Or getting on base when he was at first. Tony thought that because I was fat, I was a moron. He used to pretend to throw the baseball back to the pitcher, thinking that he was going to trick me when I took a lead. But I was a fat kid. I was used to people trying to take advantage of me in any way that they could.

What does this have to do with baseball cards?

What does anything on this blog have to do with baseball cards?

A while back I wrote about 1986 as a time when it seemed like every kid I knew was collecting cards. Before then, the only card collectors that I knew were neighborhood kids like Miller or Demetrious Danielopoulos. Or stingy ol’ Phineas when our families got together. Before 1986, collecting cards felt niche. More insular. Another thing to be scoffed at for during recess when some of us geeks would trade cards or baseball stickers for our sticker books. But by summer of 1986, it felt like collectors were coming out of nowhere. Kids with binders full of cards who looked more like investors than collectors. Kids who talked about the worth of the card over the cool photos, the design, the trivia on the back.

These bad boys were going to make all of us rich.

Great…something else to be envious about.

But the card that Tony Rizzuto had that I wanted most of all was his 1934 Goudey Gum card of Charles “Chick” Hafey.

I didn’t even know who in the hell Chick Hafey was at the time. Turns out he’s a Hall of Famer. I don’t think I would’ve even cared, had I known. That 1934 Goudey Gum card was the oldest card that I’d ever seen up until that point in my collecting life. And that Lilliputian wanker owned it? Owned it not by a trade. Not by buying the card with his own money, or digging under couch cushions for enough scratch the buy a pack of Fleer. He owned that card for the simple fact that he was lucky ass Tony Rizzuto who was good at baseball. Good at basketball. Good at football. Good enough to have all the girls like him.

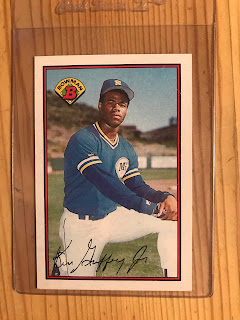

Kinda like this guy but not nearly a cool.

I don’t know why Tony brought his cards around to me. He didn’t want to trade. Didn’t even want to see my cards, which were pretty much your standard Topps, Fleer and Donruss runs from 1984-1986, thanks to my old man and stupid trades I’d made with the cards I’d ripped-off Mike Statfield. I had Sportflics for Christ’s sake.

(A brief aside…I HATE Sportflics. I

hated them back in 1986 and I hate them now. Sportflics with their stupid

moving image and dumb, puffy backs. I will never say a kind word about

Sportflics on this blog)

What was a moron who wasted any of his hard-to-come-by cash on Sportflics going to trade with a kid who owned a card from 1934? Tony didn’t want to see my cards because he just wanted to gloat. Tony wanted to let a guy, perpetually down on his luck, know how much further he could sink. It didn’t matter how many years I’d been collecting before him. It didn’t matter the time and money I’d put into the hobby. There were always going to be assholes like Tony Rizzuto out there. In the hobby. Or trying to trick me at first base.

The next time Tony came around I didn’t answer the door. I quit his ass too.

I did manage to play that whole baseball season in 1986. Even got a few hits on this one random game where the opposing pitcher was throwing so slowly that I put caution to the wind and stepped into the plate. Emboldened by my commitment, the next spring, I decided to sign up for Pony league. I was one of the younger kids on the team. The coach stuck me in right field and only let me play the last inning or so of every game. He wasn’t as impressed with my fielding. And I still couldn’t hit. All those kids who’d been taunting 11 and 12-year-olds the previous year, had turned into 13 and 14-year-olds with a newfound cruelty inside of them.

Especially Tony Rizzuto.

When my team played his, I could hear him saying stuff about me to his teammates. He even had my teammates laughing at me. I didn't need that shit from a little twerp. I didn't need that shit from anyone. It was 1987 now. I was a teeanger. The Topps, Fleer and Donruss cards that year were the best I'd ever seen. I could stay home with them. HBO was playing Stand by Me ad nauseum, and I loved that movie. Plus I still had my hat trick of TV crushes. Lisa Bonet even had her own show. Plus, there was a new crush on MTV all of the time.

So, I decided to do what I did best.

I quit.

Thanks for reading. Happy

collecting.

NEXT FRIDAY: June is Pride Month! So I’m going to do the obvious thing by bringing out my Glenn Burke cards, write a little bit about his life and career and, if I finish it, post a little bit of a review of Andrew Maraniss’ new book on Glenn Burke called: Singled Out: The True Story of GlennBurke

***Shameless self-promotion No.

1***

I too have a few new books out there. The first is my new collection of poetry entitled Eating a Cheeseburger During the End Times. It’s out on Kung Fu Treachery Press and I’m pretty proud of this one. If you’re interested you can find it HERE and HERE.

***Shameless self-promotion No.

2***

I also have a new novel out. The book is entitled P-Town: Forever and is about five members of a failed singing group getting back together in their 40s after a single they recorded 20 years ago becomes a sudden semi-hit. If you’re interested you can find it HERE and you can find it HERE, where you can also read the first chapter.

Thank you!