THE SULTAN AND HIS

TEMPLE ON THE HARLEM PLAIN:

BABE RUTH AND YANKEE STADIUM BASEBALL CARD SETS

Entrance to Yankee Stadium, New York

Haberman’s, New York, 1920s.

It was big news on April 18,

1923, when the New York Yankees opened their new digs at East 161st Street and

River Avenue in the Bronx against the Boston Red Sox.

The park was the largest and most

expensive field built to date, and the first to be called a stadium. That wasn’t good enough for one reporter, who

upped the ante and called it the “greatest of all temples dedicated to the

national game.” Another said it rose

like a pyramid.

Stadium, temple, pyramid—whatever

the appraisal, the event lived up to its billing. The pass list to the festivities had 14,000

names on it.

Gates opened at noon. Foot traffic was slow to begin, but by one

o’clock the police had their hands full trying to maintain order. At two, the grandstand was bursting at the

seams. Ten minutes later, the main gate

was ordered closed. Remaining bleacher seats quickly sold out.

Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis,

who took a late train to the stadium, had to be rescued from the throng and

escorted into the park by police.

Not everyone was lucky enough to

follow Landis through the turnstiles.

The Fire Department ordered all the gates closed at 3 o’clock with 25,000

hopeful patrons still outside the park.

A few minutes later, John Philip

Sousa and the Seventh Regiment Band played the Star-Spangled Banner while the national

flag was raised above the field.

The Yankee’s 1922 American League

pennant followed Old Glory up the pole.

The pennant won the louder cheers.

Teams and owners met at home

plate to exchange the day’s pleasantries.

Babe Ruth received a gift of an

over-sized bat.

Empire State Governor Al Smith made

news when he broke tradition with other celebrity mound artists and fired a

strike into the glove of Yankee catcher Wally Schang with the ceremonial first

pitch.

Umpire Tommy Connolly completed

the rituals by calling for the game to start.

It was also big news during the

afternoon when attendance was said to total more than 74,000. The number was later scaled back to

62,000. Either way, it was far and away

a new record for a ball game.

Inside was like “a subway crush

hour,” one witness testified, softened only by the availability of “49 million

hot dogs” and half-percent Prohibition lager at 15 cents a stein.

“The near beer was good,” noted

one connoisseur. “Even the bartenders

drank it.”

But Babe Ruth brewed the biggest

news of the day when he hit a three-run homer in the third to lead Yankees to a

4 to 1 win over his former team. The

Sporting News described the scene:

The moment Ruth's drive landed among the bleacher spectators, the crowd went mad. Hats, canes and umbrellas were thrown up and a tremendous volley of cheers greeted the smiling Bambino as he trotted around the circuit. Ruth needed just such an outburst of joy to swell his chest with pride. He had been in the dumps as a result of rather feeble hitting on the training trip and evidently was growing nervous. So when he jumped the old apple into the yawning and conveniently located stand for a jog around the bases he found himself a hero once more and was happy.

One reporter described the homer,

325 feet or so into the right field bleachers, as one of Ruth’s best, a

“terrific drive” that never rose more than 30 feet above the field.

Yankee pitcher Bob Shawkey said

the fans cheered forever.

Yankee Manager Miller Huggins

suggested the swing might propel Ruth to a 100-homer season. “He is all confidence just now. You just watch him.”

The Brooklyn Times Union

speculated the one home run might be enough to carry the Yankees to their third

pennant.

Huggins misread his crystal

ball. Ruth finished the season with 41

homers, setting a club record .393 batting average while collecting 131 RBIs

along the way.

The Times Union had the better

look. The Yankees defeated the New York

Giants 4 games to 2 in the World Series that year.

The New York Times duly

provided an account of the game, but for the Gray Lady, the stadium itself was

the real story.

“It is big,” said the paper. “It towers high in the air, three tiers piled

one on the other. It is a skyscraper

among ball parks. Seen from the vantage

point of the nearby subway structure, the mere height of the grandstand is

tremendous. Baseball fans who sat in the

last row of the steeply sloping third tier may well boast that they broke all

altitude records short of those attained in an airplane.”

The Times was in the

minority. For everybody else, the thing

was Ruth’s home run. The conviction was

especially held by the man who swung the bat.

“I’m the happiest guy in the

world,” Ruth said the morning after the game.

“I said I would give a year of my life to make a home run in the opening

game of the Yankee Stadium and I sure did make good.”

Ruth’s second wife Claire

believed the round-tripper was the proudest moment in her husband’s

career. “He definitely talked about it

more than any other homerun he ever hit,” she told one interviewer.

It all inspired New York

Evening Telegram sportswriter Fred Lieb to name the park “The House That

Ruth Built,” forever tying the man and the stadium together in the nation’s

memory.

Four particular collections of

baseball cards connect Ruth to Yankee Stadium:

·

Megacards, The Babe Ruth

Collection, 1992 (165 cards)

·

Megacards, Babe Ruth 100th

Anniversary, 1995 (25 cards)

·

Upper Deck, Yankee Stadium

Legacy Box Set, 2008 (100 cards)

·

Upper Deck, Inserts, The

House Ruth Built, 2008 (25 cards).

Megacards, 1992, The Babe Ruth Collection

Sharing a common origin, it is no surprise that the cards

in The Babe Ruth Collection closely resemble The Sporting News Conlon issues of

1991—1994. Top, Megacards, The Babe Ruth

Collection, 1992, Card 105, Sultan of Swat; bottom, The Sporting News Conlon

Collection, 1992, Card 663, promotional, Game of the Century.

Babe Ruth led an expensive,

excessive and extravagant life that sometimes crossed the border into alcoholic

debauchery.

Frank Lieb tells stories of a

detective reporting Ruth having trysts with six women in one night, being run

out of a hotel at gunpoint by an irate husband, and being chased through

Pullman cars on a train one night by the knife-wielding bride of a Louisiana

legislator. The press kept quiet. “If she had carved up the Babe, we would have

had a hell of a story,” said one scribe who witnessed the race.

His salary demands were an annual

source of debate and amusement among the sporting press.

Yankee co-owner Colonel Til

Huston tried to rein in the Babe in 1922.

“We know you’ve been drinking and whoring all hours of the night, and

paying no attention to training rules.

As we are giving you a quarter-million for the next five years, we want

you to act with more responsibility. You

can drink beer and enjoy cards and be in your room by eleven o’clock, the same

as the other players. It still gives you

a lot of time to have a good time.”

“Colonel, I’ll promise to go

easier on drinking, and get to bed earlier,” Ruth promised. “But not for you, fifty thousand dollars, or

two hundred and fifty thousand dollars, will I give up women. They’re too much fun.”

The high life caught up with Ruth

in the spring of 1925. An ulcer put the

slugger into the hospital for five weeks.

It didn’t slow him down much. In

August, he was suspended and fined $5,000 for showing up late to batting

practice after a night on the town.

That fall, Ruth admitted he had

been “the sappiest of saps” in an interview with Joe Winkworth of Collier’s

magazine.

“I am through with the pests and

the good-time guys,” Ruth declared.

“Between them and a few crooks I have thrown away more than a quarter

million dollars.”

Ruth listed a partial toll. $125,000 on gambling, $100,000 on bad

business investments, $25,000 in lawyer fees to fight blackmail. General high living cost another quarter million.

“But I don’t regret those

things,” Ruth said. “I was the home run

king, and I was just living up to the

title.”

Four dozen bats waited for Ruth

at the Yankees St. Petersburg training camp in 1928, some of the dark green

“Betsy” color that powered many of Ruth’s 60 homers in 1927 and the rest the

slugger’s favored gold. The bats

averaged 48 ounces, 6 ounces less than Ruth had formerly swung.

“At last I’ve got some sense,”

Ruth told sportswriter and cartoonist Robert Edgren that year. “I used to think Jack Dempsey was foolish to

train all the time—but Jack never got fat, did he?

“So this winter I’ve been keeping

up a mild course of training most of the time.

I’ve done a lot of hunting and on top I spend my spare time playing

handball, wrestling and boxing in Artie McGovern’s gym. But the

diet is the big thing.”

“You can’t be a hog and an

athlete at the same time,” McGovern admonished the Babe. “You eat enough to kill a horse.”

Ruth followed McGovern’s advice

that spring, slashing his meat consumption and loading up on fruits and

vegetables.

“More important,” said Edgren,

“he still has a boy’s enthusiasm for baseball.”

McGovern’s

watchful eye and the lighter lumber kept Ruth at the top of his game. So did

his marriage to the ever-vigilant Claire Merritt Hodgson. Between 1928 and 1931, Ruth homered 195 times

and drove in 612 runs.

Megacards, The Babe Ruth Collection, 1992.

Card 121, Claire Hodgson

The well-curated and

comprehensive 1992 Megacards set traces Babe Ruth’s career in 165 cards. The

set is divided into specific sections, among them year-by-year summaries of his

baseball career, his World Series play, records he established, career

highlights and anecdotes and remembrances by family members, teammates and his

friends.

Megacards, The Babe Ruth Collection, 1992.

Card 32, 1918 World Series.

It is easy to remember Ruth as

the home-run hitting hero for the New York Yankees in their seven World Series

wins between 1923 and 1938. It is less

easily remembered that he won three championships pitching for the Boston Red Sox,

the first as a reserve in 1915 and then on the mound in 1916 and 1918. His 14-inning, 2 to 1 win against Sherry

Smith of the Brooklyn Dodgers in Game Two in 1916 remains one of the greatest

post-season pitching performances in the history of the game. In 1918, Ruth won both of his starts against

the Chicago Cubs. Between the two

series, Ruth pitched 29 1/3 straight scoreless innings, a record that stood for

decades.

Megacards, The Babe

Ruth Collection, 1992.

Clockwise from

upper left: Card 9, Ruth pitches Red Sox

to 24 wins in 1917; Card 16, wins batting title in 1924 with a .378 average;

Card 22, knocks nine home runs in a week during 1930, including the longest

ever hit at Shibe Park; Card 25, drives in 100 or more runs his 13th

and last time in 1933.

Megacards, The Babe

Ruth Collection, 1992.

Top to bottom: Card 108, Ruth was the first player to hit

20, 30, 40, 50 and 60 home runs in a season; Card 92, in 1934, Ruth led a group of American

League players on a 17-game exhibition tour of Japan. A half-a-million or more fans watched the

players parade through the Ginza on the second day of the expedition; Card 94, inducted

into the hall of fame, 1939.

Megacards, The Babe

Ruth Collection, 1992, the home runs.

Clockwise from

upper left: Card 72, First Home Run; Card

77, First Home Run in Yankee Stadium;

Card 81, Babe

and Lou combine for 107 homers; Card 93,

Last Major League Homers.

Babe Ruth was a draw on the baseball field and at the box office too.

Ruth signed the biggest contract baseball had ever seen in March 3, 1927. He arrived in New York that morning on the Twentieth Century Limited at Grand Central Station from Los Angeles, where he had just finished filming a silent romance comedy, Babe Comes Home, with the Swedish actress Anna Q. Nilsson.

"I have worked harder in the past four weeks than I ever did in my life," Ruth told a gaggle of reporters. "This making a moving picture is no joke. Maybe you think it's all play, but take it from me, it is nothing but twelve to fifteen hours' hard work every day.

"I never had an hour to myself from the minute I started until I left town. I'm mighty glad the picture is finished and I am anxious to see it. I think I will make a hit as an actor."

Jacob Ruppert suggested Ruth would be better off on the diamond. It was good advice.

Image in the public domain.

Megacards, 1995, Babe Ruth 100th Anniversary

Megacards produced a 25-card set

Babe Ruth set in 1995 to mark the 100th anniversary of the legend’s

birth.

.

Megacards, The Babe Ruth Collection, Promotion, 1994,

Card 888, Beating the Odds.

Upper Deck, 2008, Yankee Stadium Legacy

In 2008

and 2009, Upper Deck marked the last season of the original Yankee Stadium by

issuing an enormous 6,742 insert set, one card for every game played at the

park or other historic sporting event that occurred on the grounds. Ruth is featured on many of the cards,

either as a representative player for the day or because of a game highlight, The

final card in the set documents Andy Pettitte’s win over the Baltimore Orioles

on September 21, 2008.

Upper Deck, Yankee Stadium Legacy, 2008. Card 6742, Andy Pettitte.

The company also issued a more

accessible 100-card boxed stadium legacy set.

Babe Ruth overshadowed all his teammates. Only Lou Gehrig pulled some of the spotlight

away from the home run king. Still, it

was a big shadow. “There was plenty of

room to spread out,” said the Yankee first baseman.

Upper Deck, Yankee Stadium Box Set, 2008. Some of the

Babe’s teammates.

Clockwise from upper left: Card 6, Bob Meusel; Card 7, Herb Pennock; Card 9, Urban Shocker;

Card 8, Earle Combs. Meusel led the

league with 138 RBI in 1925. Pennock

notched 115 wins in his first six seasons with the Yankees from 1923 to

1928. Shocker won 49 games for the team

between 1925 and 1927. The speedy Combs

scored 143 runs in 1932, one of eight straight seasons the centerfielder scored

100 or more runs. Most of the cards in

the boxed set picture later members of the Yankee fraternity.

Upper Deck, 2008, Inserts, The House Ruth Built

Upper Deck also distributed a

separate insert set of 25 cards in 2008 under the title The House that Ruth

Built. The first three cards highlight

the 1923 season.

Later in the set, an eight-card

sequence including numbers 8, 10 and 13, below, chronicles Ruth’s 60-home run

1927 season.

Yankee owner Jacob Ruppert never

completely bought the story line that Ruth built Yankee Stadium. Ruppert said Yankee Stadium was a

mistake. “Not mine,” the Colonel added,

“but the Giants.”

Alfred Mainzer, New York City

The Polo Grounds, 1937.

Simmering disputes marred the ten

years the Yankees played as a tenant of Horace Stoneham’s tenant of the New

York Giants at the Polo Grounds. The

moguls argued over playing dates, leasing fees, and future plans. In 1920, Stoneham delivered a quickly-withdrawn

eviction notice on the Yankees, convincing Ruppert to pack his team’s bags and

head across the river.

Alfred Mainzer, New York City

A flag bedecked and sold-out Yankee Stadium, 1951.

Topps 1962, Card No. 144, Babe Ruth Special, Farewell

Speech.

Major League Baseball celebrated

Babe Ruth Day at each of the seven games played on April 27, 1947 (Detroit at

Cleveland was postponed). 58,000 fans attended the event at Yankee

Stadium. The other parks drew a total of

190,000 and the ceremonies were broadcast on radio around the world. Francis Cardinal Spellman delivered the

invocation, describing Ruth as a sports hero and a champion of fair play.

On the secular plane, Ford Motor

Company gave the Babe a $5,00 Lincoln Continental. The presidents of the National and American

Leagues presented Ruth a medal on which was inscribed the message “To Babe

Ruth, whose tremendous batting average over the years is exceeded only by the

size of his heart.”

Suffering from throat cancer,

Ruth was able to muster a short farewell speech barely audible into the

microphone. “There’s been so many lovely

things said about me,” Ruth concluded.

“I’m glad I had the opportunity to thank everybody.” The New York Times said the ovation

for the slugger was the greatest in the history of the national pastime.

Upper Deck 2008, The House That Ruth Built, HRB-25.

Jersey Retired.

Almost as an anti-climax, the

Yankees retired Babe Ruth’s number 14 months later on June 13, 1948. But the cheers were still there. “He never received a finer reception,” wrote

Oscar Fraley of the United Press. “It was a roar that sounded as if the 50,000

fans were trying to tear down the house that Ruth built.”

The Sultan of Swat died an old

man at the young age of 53 on August 16, 1948.

His body lay in state for two days after his death at the main entrance

of Yankee Stadium. Tens of thousands of

fans paid their last respects to the slugger.

Megacards, The Babe

Ruth Collection, 1992.

Card 163, Game

Called.

Except where noted, all images

from the author’s collections.

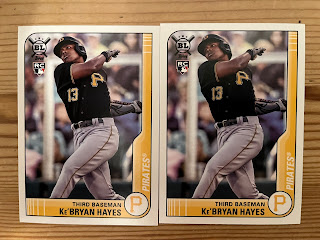

NEXT FRIDAY: Collecting on the road from Buffalo to Pittsburgh: Big League 2021...and why I'm intent on hand collating one of the ugliest sets ever.