Collecting The Negro Leagues by Russell Streur

Topps Now, Card

OS-52, 2021

.

John Jordan “Buck” O’Neil, Jr., tireless champion of Negro

League Baseball, finally gets his due this week when he is inducted in the

Baseball of Fame. O’Neill spent nearly

all of his life in the game, joking that he became an overnight sensation at

the age of 82 for his work with Ken Burns on the Baseball documentary series.

Born in 1911, O’Neill paid his dues in the Negro Leagues, breaking

in with the Memphis Red Sox of the Negro American League in 1937 before a

decade with the Kansas City Monarchs. A

three-time All Star at first base during his playing days, he then won four

Negro American League titles as the manager for Monarchs during the declining

years of Negro baseball.

Afterwards, he scouted for the Chicago Cubs, signing Lou

Brock to his first professional contract.

"He got me started on a journey that became a 19-year

major league baseball career," Brock said. "It's no wonder that baseball is

considered America's pastime. Buck was

one of its architects. He helped shape

the game.”

In 1962, O’Neil became the first black coach in the major

leagues with the Cubs. He mentored Ernie

Banks, Billy Williams and other young players during a 33-year career with the

North Siders. In 1988, he joined the

Kansas City Royals organization. In his

later life, O’Neil led the effort to establish the Negro Leagues Baseball

Museum in Kansas City, and he served as its honorary board chairman until his

death in 2006.

Some years ago, the good people at Cardboard Connection

posted a piece titled “7 Awesome Negro League Baseball Card Sets.” The un-bylined article works its way from the

Fleer Laughlin sets of the 1970s through the Ron Lewis set of 1991. A few subsets are included in the

survey.

https://www.cardboardconnection.com/guide-collecting-negro-league-baseball-cards

Here are some other sets to add to the list.

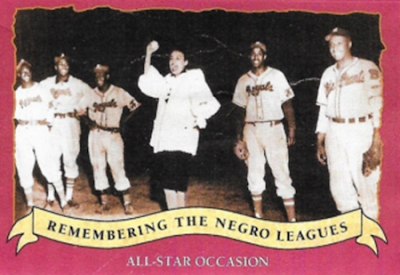

Remembering the Negro Leagues, Tuff Stuff Magazine,

September 1992

Tuff Stuff was a trading card magazine that was first

published in 1984. It enjoyed a

sometimes robust 25 years in print before surrendering to the digital

page. Along the way, the magazine

regularly featured card inserts. “Remembering

the Negro Leagues” was the topic for a nine-card set in the September 1992

issue.

None of the cards in the set featured any single

player. Instead, the set invoked the bigger

landscape of the Negro Leagues—the busses and Pullman cars, the teams, the

stadiums and the East-West games.

Unlike the white major leagues, the World Series was never

the signature event of a Negro League season.

Instead, the East-West Game brought out the glitter and the fans. Gus Greenlee, owner of the Pittsburgh

Crawfords, and club secretary Roy Sparrow, are commonly given credit for

creating the late season showpiece.

Debuting just two months after the first white All-Star game

was played in 1933, the East West spectacle was an instant hit. Almost always played at Comiskey Park in

Chicago, the game became the most important event on America’s Black sports

calendar. The Union Pacific added extra

railroad cars to accommodate the fans flocking to the Windy City. In 1944, the East West game outdrew the white

All-Star game, and more than 50,000 fans attended the event in 1945.

“That was the glory part of our baseball,” said Sammy

Hughes, chosen in 1937 from the Washington Elite Giants as the second baseman

for the Eastern team. “It was an honor

to be picked even if you were just gonna sit on the bench.”

Exhibitions between black and white teams also drew big

crowds. Singer, actress and Civil Rights

activist Lena Horne is pictured on Card 8 of the Tuff Stuff set, throwing out

the first pitch in a 1945 game between nines from each side of the color

line.

1933 Negro All Stars, The Sporting New Publishing Co., 1988

Clockwise from upper left: Willie Wells, Oscar Charleston, James “Cool

Papa” Bell, William “Judy” Johnson.

The title of this small collection suggests that it consists

of players from the inaugural 1933 East West game. The hint is partially true—seven of the

players on the unnumbered 12-card set were selected for the September 10

event.

First baseman Oscar Charleston of the Crawfords received the

most votes in 1933 with 43,793 ballots.

Pitcher Willie Foster of the American Giants followed with 40,637. Foster rewarded the fans with the only

complete game in the game’s history, an 11 to 7 win for the West. George “Mule” Suttles supplied the power for

the winning side with a home run, a double, two runs scored and three RBIs. Of the three stars of the game, nly

Charleston is included in the set.

Photography is attributed to Charles Martin Conlon, but the

set does not come anywhere the precision or the production quality of the

Conlon Collections of the white major leaguers issued in the early 1990s.

What Could Have Been, Inserts, Topps, 2001

Clockwise from upper left: Ray Dandridge, Card WCB9; Walter “Buck”

Leonard, Card WCB3; William “Judy” Johnson Card WCB7; George “Mule” Suttles Card

WCB8

The ten Topps What Could Have Been insert cards from 2001

cover many of the same players and does a better job of image selection and

production than the Sporting News set.

The Negro League Baseball Players Association Give-Aways,

1992

Clockwise from

upper left: Bill Wright Card 12, Edsall “Big” Walker Card 11

Martinez “Skippy”

Jackson Card 18, Sam “The Jet” Jethroe Card 10

Baseball runs deep in the anthracite veins of Lackawanna

County, Pennsylvania. Dozens of players

from the county played the big-league game, and two Hall of Famers are buried within

its borders: long-time Detroit Tigers

manager Hughie Jennings and American League umpire Nestor Chylak. Even with the heritage, it’s a remarkable

statement that the fan give-away at the minor league Scranton Wilkes-Barre Red

Barons game on August 9, 1992, was an 18-card set of Negro League players

produced by Eclipse Cards and sponsored by Kraft General Foods. Painted by artists Jon Bright and John Clapp,

the set includes well-known names like Leon Day, Double Duty Radcliffe, Buck

Leonard and Josh Gibson as well as less famous players.

Martinez Jackson played second base for the Newark Eagles in

the 1930s before opening a tailor shop in Philadelphia. Baseball ran deep in Jackson’s veins, too,

all the way to Cooperstown. He’s the

father of Reggie.

Sponsored by Eclipse

Enterprises and painted by Paul Lee, the four-card set pictured above was a fan

give-away at Shea Stadium on June 2, 1992.

https://www.ebay.com/itm/144279869489

Josh Gibson Inserts Topps 2007

Granted, a 110-card set based on Josh Gibson’s home runs was

never going to be an easy task. The lack

of records for games played by Negro League teams makes it impossible to come

anywhere near a true figure for Gibson’s total, much less a chronological

progression. But even left with just a

fraction of the whole, there are numbers that can be documented. Hank Aaron hit a home run every 16 at

bats. Gibson hit one every 13 in

official records. Gibson’s lifetime

batting average of .374 is better than Ty Cobb’s mark of .366. A 12-time All Star, a four-time batting

champion, and the universally acknowledged home run king of Black baseball.

And there’s testimony.

Hall of Famer Monte Irvin said "I played with Willie Mays and

against Hank Aaron. They were tremendous players but they were no Josh

Gibson." Hall of Famer Roy Campanella said Gibson was, "not only the

greatest catcher but the greatest ballplayer I ever saw." When Barry Bonds was asked about holding the

home run record, Bonds replied, “No, in my heart it belongs to Josh Gibson.”

That’s just on the field.

There’s also his life. The death

of his wife giving birth to twin children, his own health problems, and his

dejection over not being chosen to integrate the major leagues after World War

Two. “I think that’s one of the reasons

why Josh died so early,” said Larry Doby.

“He was heartbroken.”

But Topps gives us little of this—just the same picture on

all 110 cards and the same brief bio on the back. Only the numbers change. It’s a shame.

Front Row, 1992

In contrast, a pair of limited-run, five-cards sets issued

by Front Row in 1992 includes player statistics on one card and biographical

sketches on the other four. Each offers

an example of what Topps could have done with the Josh Gibson set, had Topps

been truly invested in the offering.

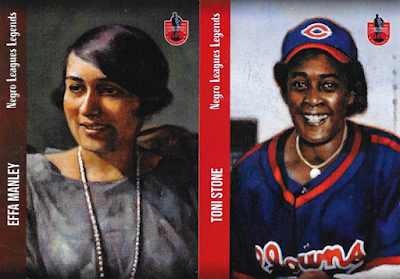

Negro Leagues Legends,

2020

If there’s one set of Negro League baseball cards to have,

this is the one. Commissioned to mark

the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Negro National League,

this 2020 issue of 184 cards is the most comprehensive set of Black baseball

cards published to date. Painted with

grace and a sure hand by baseball artist Graig Kreindler, the set includes all

the Negro League greats but really gains its worth by the wider net it

casts.

There’s a story worth knowing on every card.

Clockwise from

upper left: Lazaro Salazar, Card 60;

Perucho Cepeda, Card 27; Ramon Bragana, Card 114; Estaban Bellan, Card 156.

Players from the Mexican and Dominican Leagues and the Cuban

and Puerto Rican Winter Leagues are included too. Chief among the Latin players and managers

are Lazaro Salazar, who eaned batting titles in three countries, won 150 games

as a pitcher, and managed clubs all over Latin America to 14 league

championships; Pedro Anabal “Perucho”

Cepeda, patriarch of the major league Cepeda clan; and Ramon Bragana, elected

to both the Cuban and Mexican Baseball Halls of Fame. Though white, Estaban Bellan is included in

the set for his role in establishing the game in Cuba.

Left: Effa Manley, Card 148. Right:

Toni Stone, Card 167.

Two women are included in the set: Effa Manley, the formidable owner of the

Newark Eagles and the only woman in the Hall of Fame; and Marcenia Lyle “Toni”

Stone, who played as a teenager for the barnstorming Twin City Colored Giants

and in later years with the San Francisco Sea Lions of the short-lived West

Coast Negro League and the New Orleans Creoles of the Negro Southern League

before finishing her career on the diamond with the Indianapolis Clown and the

Kansas City Monarchs.

Left William

Lambert, Card 83. Right Unknown Player,

Card 128.

Organized baseball was segregated for decades, but military

teams did not always follow suit.

William Lambert, who pitched the integrated team of the USS Maine to the

Navy championship in December of 1897, died along with most of his teammates

when the battleship blew up in Havana harbor a month later.

The most poignant card in the set is the Unknown player,

symbolizing all the Negro League players whose names and stories have been lost

to time.

Minnie Minoso (Card 120, left) and Moses Fleetwood Walker (Card

110, right) also among this year’s inductees, are also included in this set. It’s a home run collection, a mighty Josh

Gibson clout of a set. It will be hard

to top, and definitely recommended for anyone interested in the history and

players of the Negro Leagues.

Buck O’Neil. (Left) Negro Leagues Legends, 2020, Card 176;

(Right) Negro Leagues

Legends, 2020, Card 184.

Fleer, Greats of the

Game, 2001, Card 119

Play on, Buck.

PITTSBURGH PIRATES NEGRO LEAGUES STARS GIVEAWAY 1988

The Philadelphia Phillies played

the Pittsburgh Pirates in a game at Riverfront Stadium on September 10, 1988. Ron Jones homered for the visitors in the

Saturday night affair but defensive miscues by his teammates gave the Pirates

all the help they needed to overcome the swing.

Dave LaPoint pitched all nine innings and picked up his seventh straight

win and 14th of the year as the Pirates prevailed, 5 to 1.

1988 marked the 40th

anniversary of the last World Series played in the Negro Leagues, won by the

Homestead Grays over the Birmingham Black Barons, four games to one. By that time, the Grays were playing most of

their home games out of Griffith Stadium in Washington, D.C., but the team’s origins

were all Pittsburgh and the club still maintained deep ties to the Steel City.

Regardless of the Grays home

address at the time, Black baseball owned a rich tradition in Pittsburgh. The Grays themselves hailed from Pittsburgh’s

Homestead neighborhood. In the 1930s,

the Pittsburgh Crawfords emerged from the Hill district and powered their way to

three league pennants. The Pirates, in

partnership with the Duquesne Light Company, celebrated Negro League baseball that

late summer night at Riverfront, presenting a plaque honoring the Grays and

Barons to the city and giving away a set of baseball cards to the fans.

The set was one of the earliest

ever produced on Negro League players, preceded only by the two Fleer Laughlin

sets in the 1970s and the Fritsch collection of 1986.

Narratives on the backs of the 20 cards were written by Rob Ruck, then a professor of history at Chatham College and now a professor at Pittsburgh University. With images obtained from the National Baseball Library, the Carnegie Library and private individuals, the cards tell the story of Black baseball in Pittsburgh from the beginning of the 20th Century to the demise of the Negro Leagues.

For the first time, Negro League team pictures were shown on baseball cards, including rare images of early Grays and Crawfords clubs. The dates of the photographs only hint at the long history of Black baseball in Pittsburgh.

Left to right, front

row: Ben Pace, Jerry Veney, Emmett

Campbell. Middle row: Pete Peatros,

Eric Russell,

Cumberland Posey, Sel Hall, John W. Veney, Bob Hopson, Hubert Sanders.

Back Row: Henry Saunders, Sam Smith, B. F. Alexander,

Roy Horne, Ralph Blackburn.

Left to right, front

row: William Smith, Tootsie Deal, ?

Julius, Wyatt Turner, Reese Mosby, Bill Jones, Tennie Harris, Johnny Moore.

Back row:

Nate Harris, Bill Harris, Harry Beale, Buster Christian, Jasper Stevens.

The Grays

were one of the longest-lived Black ball clubs. Formed in 1900 as the Blue

Ribbons, the team renamed itself the Homestead Grays in 1910 and became a

popular club on area diamonds, due in no small part to its talent. In 1913, the Grays played their way to a

42-game winning against the local competition.

Cumberland “Cum” Posey worked his way from player to manager to owner of

the team. Posey guided the Grays as an

independent club until joining a rebuilt Negro National League in 1935.

The Grays were declared league champions in 1937 and 1938. During the

years of World War II, the Grays increasingly shifted operations to Washington,

DC, pulling in larger crowds at Griffith Stadium than at Pittsburgh’s Forbes

Field. Under the field leadership of team captain Buck Leonard, the Grays

won six more pennants before the league disbanded at the end of the 1948

season. Leonard's 15 years with the Grays was the longest stint of any

player with any team in the history of the Negro Leagues.

Players from two schools in

Pittsburgh’s Hill District, McKelvey and Watt, formed the nucleus of the

Pittsburgh Crawfords in the mid-1920s.

In 1926, the team won the city’s recreational league championship. By the end of the decade, the schoolboys had

become young men and the team rose to the top of Pittsburgh’s sandlot baseball

ranks. Hill District nightclub operator

and numbers king Gus Greenlee bought the Crawfords in 1931 and raided the Grays

and other clubs to replace the neighborhood roster with future Hall of Famers

including Oscar Charleston, Josh Gibson, Judy Johnson and Cool Papa Bell. Unhappy with the rent charged at Forbes,

Greenlee built and named for himself a concrete and steel stadium that seated

7,500 spectators. It was home to the

Crawfords until Greenlee sold the club off after the 1938 season. The Crawfords won three pennants of the

revived Negro National League between 1933 and 1936.

Some diamond historians consider

the 1935 version of the Crawfords to be the best ever in the history of the

Negro Leagues. Others give the nod to

the 1931 Grays. Oscar Charleston and

Josh Gibson played on both clubs.

While many of the cards on the

give-away set portray Hall of Famers with national reputations, two cards

recognize Pittsburgh players vital to the development of baseball in the

city.

Willis Moody and Ralph Mellix are

seen shaking hands on one of the cards.

As Ruck states on the back of the card, not every local team followed

the Grays and Crawfords into the Black professional leagues. While Moody and Mellix each played on the

Grays, the truer legacy of the men comes from their decades with the 18th Ward,

a team that represented Pittsburgh’s Black Beltzhoover neighborhood.

The Reverend Harold “Hooks” Tinker played in Pittsburgh’s

industrial leagues, on the sandlots, and was a member of the Crawfords before

finding a place behind the pulpit. He

never strayed too far from the diamond, becoming manager of the Terrace Village

housing project team in the 1950s and leading the integration of Pittsburgh’s

sandlot clubs.

The set was distributed to fans

on a folded 10” by 19” inch sheet with perforations to separate the individual

cards. Ruck tells the fuller story of Black

baseball in Pittsburgh in his book, Sandlot Seasons:

Sport in Black Pittsburgh (University of Illinois Press, 1993). He is also the author of Raceball: How the Major Leagues Colonized the Black and

Latin Game (Beacon Press: 2011), The Tropic of Baseball: Baseball in the

Dominican Republic (University of Nebraska Press,

1999) and other books.

Checklist

1 Rube

Foster

2 Homestead

Grays

3 Cumberland

William “Cum” Posey

4 Pittsburgh

Crawfords (1926)

5 William

“Gus” Greenlee

6 John

Henry “Pop” Lloyd

7 Oscar

Charleston

8 Smokey

Joe Williams

9 William

“Judy” Johnson

10 Martin

Dihigo

11 Leroy

“Satchel” Paige

12 Josh

Gibson

13 Sam

Streeter

14 James

“Cool Papa” Bell

15 Ted Page

16 Walter

“Buck” Leonard

17 Ray

“Hooks” Dandridge

18 William

Moody and Ralph “Left” Mellix

19 Harold

Tinker

20 Monte

Irvin

--Russell Steur

Thanks

for reading! Happy collecting!

Next

Friday: Card Pick-ups from my trip to Pittsburgh