I have one undeniable card

collecting truth.

I

will never own a Jackie Robinson card from his playing days.

Okay,

this isn’t set in stone.

And

it’s not undeniable.

But

it’s pretty damned close.

I

found myself perusing ComC the other day, as many of you might be doing right

now, or after you read this post. I was doing what card collectors do: I was buying

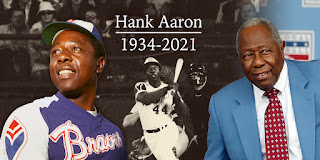

cards. My Henry Aaron post inspired me to actually begin building up my Aaron

collection. I found a 1972 Topps Aaron, whose card condition I could live with.

While on ComC I decided, for shits and giggles, to take a look at Jackie

Robinson cards.

That

was a quick trip.

For

the record, whenever I’m on ComC I choose two filters. I choose “ungraded” and “buy

now.” I don’t have any issues with people who choose to get cards graded. It’s

just not my style. Nor am I a fan of “gambling” so I tend to want to buy my

cards outright. I shouldn’t call buying cards on auction or bidding as being

gambling. A lot of collectors get cards they want affordably by doing that. I tend

to have a real Charlie Brown view of my life, and don’t view winning in most

cases as being an option.

With Jackie

Robinson cards from his playing days, it really didn’t matter how I filtered.

Graded/ungraded. Buy now/auction. I wasn’t going to be able to afford one

anyway. That ship has essentially sailed. The stuff I could remotely afford,

even I wouldn’t want to buy the card in that condition.

And my standards

aren’t too high.

A Clemente is a Clemente.

And a pipe dream is a pipe dream, right?

Still…

I

suppose I should answer as to why I’d want Jackie Robinson cards in my

collection. Or maybe the question is, why wouldn’t a collector want Jackie Robinson

cards in their collection? Jackie Robinson is baseball history personified. His

statistics, historical documents of the times. His cards of that era, the same.

This isn’t anything a baseball fan or a card collector doesn’t already know. Jackie

Robinson is a cultural hero. He’s a hero to baseball as well. The sport retired

his damned number! In a sport full of Ruths, Gehrigs, Aarons, Mays, and

Clemente, Jackie Robinson still stands heads and shoulders above them all.

Okay,

maybe Babe Ruth is debatable.

And

I can’t afford his cards either.

All

the same because of his stature and talent, it be cool to have cards from

Jackie Robinson’s playing days in my collection.

But

it’s not going to happen.

It’s

undeniable.

At

least right now it is.

Maybe

I’ll start playing the lottery today.

If

I want Jackie Robinson cards in my collection, I have to rely on cards like the one above.

Or

this.

One of only two Project 2020 cards that I bought.

I’ve

said, more times than you want to read, how much I like post-career playing

cards for players. I love seeing players like Henry Aaron, Jackie Robinson, or

Roberto Clemente in the designs from my youth. I also enjoy seeing today’s young

stars like Vlady Jr. or Yordan Alvarez on design from before their time. Their

great in sets like Heritage and even more so in sets like Archives, that blend

the past and present together on a number of designs.

I

even like seeing the old timers in Stadium Club.

Like American Badass Eddie Murray.

I

do with a few.

Mainly

Clemente, Willie Stargell and Henry Aaron.

I

won’t be adding this Will Clark card to my collection.

Will Clark already had a 1987 Topps card.

I do collect Jackie Robinson post-playing day cards, however. Or, if I don’t collect them, I at least keep all of the ones that I get as inserts in packs or in boxes, or I keep the doubles from sets like Stadium Club or Archives. The answer is obvious as to why. These cards are the closest I’m going to get to actual Jackie Robinson cards.

And,

yes, I do this for Babe Ruth too.

But

this isn’t a blog post about him.

Admittedly

my collection of Jackie Robinson cards is a modest one.

My latest Jackie

Yep, that’s almost everything.

I

even have some ephemera from when Jackie’s number was retired by Major League baseball.

I forgot there was a reprint of Jackie’s 1948 Leaf card inside.

I

guess I own me a Jackie Robinson “rookie” card.

July

12, 1997. That was when the Pirates officially retired Jackie Robinson’s number

42 in a pre-game ceremony in front of 44,000 fans. I didn’t attend this game,

though I attended a good many in 1997. My old man did and figured maybe the items

would be in good hands with me. I’ve held on to them for twenty-five years. The

game was wild too. Francisco Cordova and Ricardo Rincon threw a 10-inning no

hitter against the Astros, and won on a home run by Mark Smith.

The

1997 Pittsburgh Pirates were dubbed “The Freak Show.”

They

almost won the division with a 79-83 record.

1997

was the first season that I really got back into Pirates baseball after they

broke my heart in the 1992 NLCS.

I’d

spent from 1993-1997 pre-occupied with college and women.

I

was probably having women troubles on July 12, 1997, if memory serves me correctly.

But

this isn’t a blog post about that either.

Living

in Brooklyn, there’s a lot Dodgers history still around. You can visit the one

remaining wall to Ebbets Field at the Ebbets Field apartments. A number of

homes that players owned are still around. One owned by Duke Snider is in the

actual neighborhood where I live. The Mets jack Brooklyn Dodgers history

whenever they can. And Jackie Robinson, himself, is buried in the Cypress Hills

cemetery, here in Brooklyn. A long, long way from Pasedina.

So,

there is that aura that still surrounds him here in New York City.

During

the initial quarantine stretch of the never-ending pandemic, when baseball was

supposed to be happening, but wasn’t happening, I comforted myself by reading a

number of books on baseball and biographies on baseball players. One such book

was Arnold Rampersad’s excellent biography on Jackie Robinson.

Not only does Rampersad do an excellent job of showing what Jackie Robinson went through breaking into the Major Leagues as the first player of color, the book does a fine job of detailing Robinson’s post-playing life as well. Jackie spent more years as an executive for Chock Full O Nuts than he ever did with the Dodgers, and he had contact and connections with everyone from Dwight Eisenhower to Malcolm X.

The

Rampersad book pushed me deeper into Jackie territory and was the catalyst for

me beginning to pull his cards from my insert boxes, and to put them in a

proper player place in my PC. If it is undeniable that I’ll never own a true

card from Jackie Robinson’s playing days, then it is almost certain that the

Topps Company has put an over-abundance of Jackie Robinson post-career cards out

into the collecting world. Archive cards. Stadium Club cards. Base Set Short

Prints.

Even

Panini has gotten into the act.

I don't often buy Panini products, but when I do it's Diamond Kings.

It’s

true we don’t know what Topps is going to do going forward since they were

acquired by Fanatics after the licensing debacle of last year. I guess as

collectors we can assume Topps base product will still exist. But what of the

others? Over the previous weekend I was listening to John Newman’s Sports Card

Nation. His guest for that show was Joey “Dub Mentality” Shiver.

It

was a good show.

John asked Dub

what his hopes were for Topps going forward after the acquisition by Fanatics. Dub

was pretty impartial and willing to give Fanatics and honest shot. But he said

one thing that stuck with me. And that was his hope that Fanatics would pay

attention to the Topps legacy. Now, I guess this can mean whatever you want it

to mean. That Topps continues to put creative ideas into the base cards. That they

come up with something new and exciting for collectors that still feels very

Topps. For me, I hope that Topps/Fanatics keeps some legacy products going. I hope

Heritage stays. I hope Archives stays too.

And keep those

cool inserts coming.

My Jackie Robinson collection can only grow from there.

2022 Topps Series 1:

Despite

all of my talk about quality vs quantity, it was inevitable that I was going to

buy a box of 2022 Series 1 Topps base cards. I’m glad I did. I actually bought it from this place.

I was a pretty big fan of the MLB Flagship store when it opened in summer of 2020. Of course, in summer of 2020 I was a fan of anywhere that I was actually able to get out of my neighborhood and go to. The MLB Flagship store was pretty egalitarian at the beginning. You could find merchandise for every single Major League Baseball team. That has, sadly, since changed, and the store caters more to the New York/L.A./Chicago/Philly/St. Louis brands.

But

they do have a Topps section that sells cards at retail prices.

So

I bought this.

First off, I’m a big fan of the 2022 base design.

It might be my

favorite base design since I got back into collecting in 2019. The borders are

crisp. The photos are sharp. You can actually read the player’s names this

year. I love the team color lacing as

well, and how it makes the photos really stand out. Just top-notch base work.

As for the bells

and whistles, or what others like to call the inserts.

This showed up.

I’ve never pulled an auto in a Hobby box. I was waiting for my requisite game-used fabric patch card, but the Mr. Ryan showed up. That said, I’m not an auto collector. If retail boxes came out the same day as hobby boxes I’d buy them instead. I’m in it for the fun in opening and enjoying base. With the Ryan, and even the Tatis Jr., well, I don’t sell cards, so I’m probably going to see if I can trade with someone. The problem with that is, I tend to want vintage. Clemente. Aaron. That kind of stuff. So I’ll probably be holding on to the Ryan and Tatis for a while.

These inserts get

my vote for least essential cards of the year.

Overall it was a fun rip

Thanks for reading! Happy Collecting!

Speaking of the "Freak Show" the folks over at SABR have a fine little article about that July 12, 1997 game which you can read right HERE.

You can listen to the episode of Sports Card Nation with Dub Mentality right HERE

I actually found myself on a Podcast. I was on episode 190 of About the Cards. Thanks to Ben and Stephan for having me on! You can listen to that HERE.

NEXT FRIDAY: We're going back in time. I'm going to be talking about youth. Young love. Labor